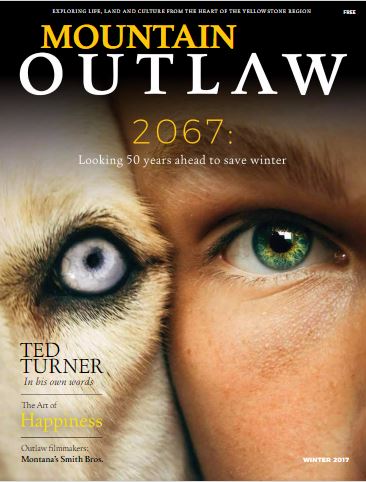

Mountain Outlaw Magazine

By: JOSEPH T. O’CONNOR

To many, Ted Turner, the adopted Montanan dwelling in our own backyard, is a bit of a mystery, a man who has led two lives. The Cincinnati, Ohio, native cut his teeth on business ventures of near-epic proportions. He founded the CNN and TBS television networks, owned the World Series-winning Atlanta Braves, and for a time headed the World Championship Wrestling company. A fiercely competitive media mogul with a tongue capable of setting the room ablaze, Turner earned a reputation for being as tenacious as his 61-foot racing yacht of the same name that won the infamous Fastnet Race in 1979.

But in the late ‘70s another side of Turner began to emerge. A mentor to Turner, one Jacques Cousteau, helped impart in him a notion of altruism. Indeed, Turner saw Cousteau the explorer and conservationist as a leader of men. “The Captain should rightfully be considered the [environmental] movement’s father,” he once said. In 1977, Turner read a report commissioned by President Jimmy Carter outlining the dire straights the world was facing. Without comprehensive change, the report noted, these problems could spin out of control.

“It drove home the point to me, for the first time in my life, that, as a business person, the decisions I make can either contribute to making problems for the Earth worse, or they can help advance a solution,” Turner told writer Todd Wilkinson in the 2013 book Last Stand: Ted Turner’s Quest to Save a Troubled Planet.

These days, the entrepreneur-turned-mogul-turned-philanthropist is worth $2.2 billion. He still wears his moustache reminiscent of Clark Gable in Gone With the Wind, and puts his time and a famously restless energy into searching for solutions to the biggest issues facing the world today. Turner has founded five foundations, including the Turner Endangered Species Fund, and the Nuclear Threat Initiative.

In 1997, he pledged $1 billion to the United Nations, which, in turn, launched the United Nations Foundation dedicated to tackling worldwide concerns, among them global poverty, climate change, women’s empowerment and energy access. The event, in fact, was a challenge to other wealthy individuals to give more, and it resonated with the likes of Bill and Melinda Gates, as well as Warren Buffett.

Turner, who turned 78 in November, is the second-largest private landowner in America, and has put much of it in conservation easements, ensuring its natural existence in perpetuity. He owns 15 ranches in the western U.S., of which four are in Montana. The 113,600-acre Flying D between Bozeman and Big Sky is managed for wildlife and bison. Turner is dedicated to the West, its land and its native animals, owning the world’s largest private bison herd. But he’s also loyal to bettering the world at large.

The one-time “Mouth of the South” (don’t call him that) has made an impact on sustainability and environmentalism considered among the most impressive in modern history. He’s been called a provocateur, a capitalist, a crusader. One thing you can call him: humanitarian.

Turner granted Mountain Outlaw an exclusive interview in November. Here are his words.

MOUNTAIN OUTLAW: You bought your flagship Montana ranch, the Flying D, in 1989 and from there grew your landholdings in the U.S. and Argentina to more than 2 million acres, and expanded your bison herd to more than 51,000. Few people imagined this could be done. How do you feel about it looking back?

TED TURNER: I’m proud of what we have accomplished; it’s been a real team effort. In the beginning, I was on a steep learning curve because we set out to do something that had never been done before: bring back bison on a massive scale. In order to do that, we needed a lot of land. Fortunately, I had the economic resources to acquire properties that could accommodate an expanding herd. Now, here we are decades later and the bison is our national mammal.

M.O.: You were excited when a wolf pack began denning at the Flying D, and it now sounds like a sow grizzly and her cubs are living fairly close to your house. Are you equally as excited about having bears living not far from your backdoor?

T.T.: I hired Mike Phillips, who previously led the effort in the mid-‘90s to restore wolves to Yellowstone Park, to oversee the daily operations of the Turner Endangered Species Fund. He told me that if we provided habitat on the Flying D, the wolves of Yellowstone would eventually find their way to the ranch. When wolves established a pack, I was overjoyed. I think we may have been one of the first, if not the first, ranch in the West to lay out a welcome mat for wolves! I have literally howled to wolves off the back deck of my house with my family and friends.

M.O.: When you arrived in Montana, development was really starting to take off and the easement you placed on the Flying D was one of the largest of its kind. Had the ranch not been protected and instead sold as a real estate play, it would look very different today, and you left a lot of money on the table by embracing conservation. What motivated you?

T.T.: Respect for nature and the environment. In so many parts of the country, wildlife is getting crowded out by people and development. When I first laid eyes on the Flying D, it didn’t take me long to realize how special it is; and I knew that if it wasn’t protected, it would turn into a giant suburb of Bozeman, just as other parts of the Gallatin Valley have. I view land ownership this way: What’s important is not only what you take away from the land, but also what you do to make sure these lands endure over time.

M.O.: In Wilkinson’s book, you make the analogy that the world is currently in the seventh inning and the home team is down by a couple of runs; that now is the time to rally. What keeps you up at night?

T.T.: Potential nuclear dangers are my top concern. The U.S. and Russia still have large nuclear arsenals pointing at each other, and we must also consider what North Korea is capable of. Human or computer error could trigger an event that leads to an exchange of nuclear weapons, and it would be catastrophic. [Former U.S. Senator] Sam Nunn and I founded the Nuclear Threat Initiative 15 years ago to address these issues, and NTI is doing some outstanding work. After nukes, I would say climate change, addressing human poverty and population growth, and loss of biodiversity rank right up there. Many of these issues are so interrelated, and I should note they all have environmental components. Degraded environments cause people and countries to become desperate, and when you’re desperate, you don’t always behave rationally.

Click here to read the full Montana Outlaw article.